I will be taking a break for a couple of weeks from posting to this blog; I will be in the mountains of Washington State for a week (without internet connection) and then going to Ontario for a couple of weeks — once in Ontario I will be able to post.

For this post, I wanted to start with the skill that is essential to human development, that of awareness. It is the primary skill of Gestalt Therapy. It is not what most people think it is — it is not thinking; it is sensing.

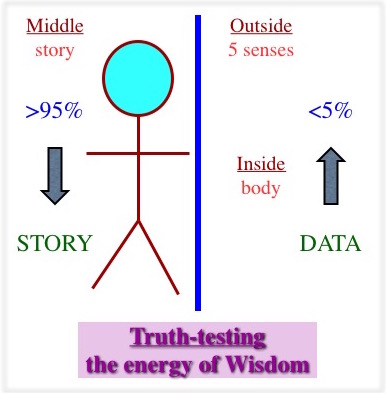

Simplistically human beings can attend to three areas of experience: Outside the body (the so-called five senses, although there are more), Inside the body (muscle and joint experiences such as temperature and proprioception, also known as location in space), and Middle (the meaning/story we give to these sensory experiences — we generally call this thinking). Nobody gets away without story and somewhere in my past I recall a statement that most people spend more than 95% of their time experiencing Story and less than 5% in Data (the combination of Inside and Outside. Even if this is increased to 10% attention to Data, the change is very significant. This is what Fritz Perls, the originator of Gestalt Therapy, called Awareness — attention to one’s spontaneously emerging perceptions; he also noted that “Awareness in and of itself is therapeutic.”

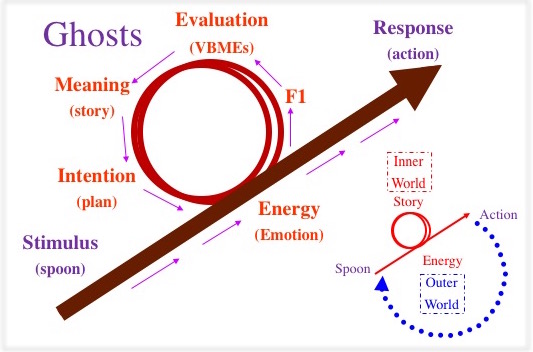

I’ll return to this in a moment; first I want to introduce what I call the Action Model. Something happens in life, a Stimulus (often I call it a Spoon that stirs the Pot — see a later Post). As I am sure all readers know, biological creatures move from Stimulus to Response. In between, we human beings have this marvellous processor called the Mind[1]. Through a variety of iterative processes, sensory awareness of the Stimulus is perceived (usually called the F1 state, the earliest sensory date of which I can be aware); evaluated by my values, beliefs, memories and expectations (my VBMEs); and given meaning as my Story. My response to this meaning is developed as a plan of Intention, feed into life energy (principally called Emotion) and turned into my Response, my action back into the environment. Thus, I shift from the inner world of Meaning to the outer world of Energy.

Essential to under-stand [sic] is that I never respond to the Stimulus; I respond to the meaning I give to the Stimulus. To emphasize this, I call the meaning my Ghost (of the stimulus)! Because of the many intervening filters, it is also essential to under-stand that my Ghost is not the same as your Ghost, even for the ‘same’ Stimulus. If you the reader can grasp this, much of the conflict in your life will disappear.

Returning to the Action Model diagram, there are three places I as therapist can intervene (or, with enough awareness, you can intervene). I can work to change the meaning you give to your experience; I can work to change how you evaluate your experience (for example, your beliefs or values); or I can work to change the primary sensory awareness you bring to your experiences. The closer I can get to your primary sensory awareness, the more profound the change — this is one aspect of ‘Awareness in and of itself is therapeutic.’ It is also a component of how awareness becomes the basis of knowing my own wisdom; on a later post, we will explore how this becomes the ability to test our own truths.

An example may help. As a therapist, I have two primary intentions when working with a client. First is to establish trust so that the client will be willing to explore with me. The major skill here is my ability to have empathy and compassion for the struggles of the client. Fundamentally I have no judgment about the client; I truly believe that all clients are always[2] doing the best they can. That said, my second job is to challenge the client to explore the issues with which they struggle (all of us are pain avoiders, and thus at some level we resist going to therapists). I challenge but I never push.

Suppose a client and I are working together, and the client says: “Dave, don’t push me.” They are stating their truth! They perceive they are being pushed. My question though is how can I know if I am pushing or not. Through years of training in awareness, I monitor my body as to what I am experiencing in my sessions. I know from past experiences of when I am invested in the client’s change (when I am pushing), I develop tension in the small muscles between my eyebrows; when I am not pushing, when I am simply exploring and/or offering suggestions, I have no tension there.

So, if the client says, “Don’t push me,’ I review my awareness of this sensation. If there is tension, I apologize to the client, agreeing that this is not a good intervention, and back off. If however there is no such tension, I will say something such as “Apologies, I didn’t realize I was” (validating the client’s experience) yet knowing full well that I was not pushing. Meanwhile, this is an opportunity to assess what might be happening to the client such that they feel pushed even though I am not pushing. Over the years, this has proved to be a very powerful use of awareness.

So, how to develop awareness. When I started my Gestalt training years ago, the instruction was to practice the stem sentence “Now I am aware of …” and complete it with a specific experience — the tip of my Rt Index finger, the sound of scraping, the dryness of my upper lip, the tension in my left ankle, the sound of a car passing in the street, et cetera. Sensory experience, inside or outside my body, as specifically and simply as possible[3]. I did that 20 minutes a day, twice a day, for six months. I would do it at bus stops, sitting in a restaurant, anywhere I had the opportunity to develop the skill. Then I started going to Buddhist retreats[4], called Vipassana retreats, where we practiced awareness 14 hours a day, either sitting or walking, furthering the development of awareness in profound ways.

[1] A footnote: Modern neurobiology considers the processor to be the Brain. In part I agree with this concept, yet I am convinced that the Mind is much more than the Brain. However I am not certain how and where to draw the boundaries between Mind and Brain. Thus I will often talk about the Mind-Brain when I lack clarity.

[2] I seldom use words such as always or never. There are exceptions. some intended, some unintentional.

[3] Such sensory experience is never free of story, yet the intention is to be as clean as possible.

[4] Buddhism per se is not a religion; it is a study of awareness developed over 2500 years of practice. It can be dogmatic yet for the most part it is a study of consciousness. Vipassana retreats are often at minimal cost or entirely free, the attendee leaving donation at the end.

Leave a reply to usuallybouquet716319fce1 Cancel reply